Introduction

I’m briefly introducing this text as it is taken directly from a supplement I recently published with TQ#15. It was quite spur of the moment, having wanted to try and collect some of these thoughts for a while now, so I contacted Andy and he was up for it and it all came together quite quickly. It’s likely to be out-of-date quite soon, but it does represent a current snapshot, of the problematic flows of power and capital that run through our practices of recording and releasing music on-line.

Here is a PDF of the supplement, or an ePub ebook and below is the text itself.

Releasing Music in the NAU

This international music community we call the No Audience Underground (NAU)1 thrives upon small-scale publishing. From micro-labels dropping cash on short runs of vinyl, to home burned 3” CDrs. Rather than opposite ends these are part of a continuum, also embracing tape-trading, mail art, craft forms, and co-operative organisation. I have avoided mentioning digital, but artists have varied widely from downright avoiding digital formats and social media, to leading the charge with download codes, streaming platforms, and online communities.

What I feel is true, of both physical and digital forms of production within the NAU, is that there’s ZERO cynical ‘business’ only operators. People care about what they are doing and make choices that best fit contributing positively within the scene. That doesn’t exclude anyone from wanting to turn a profit – though it’s uncommon – but it’s generally of the, “so I can fund more releases and/or make this my day job,” variety.

The general path most of us follow, in putting some music out into the world, means that we will likely brush with DIY2 publishing. For most the online/digital cat is well and truly out of the bag – refusing it completely is simply not a viable option and we must consider digital publishing and distribution of our works.

Some stubbornly follow/disrupt format trends, package releases as totemic objects, make things cheap and basic, use recycled and ethical materials, expand notions of formats through creative combinations of downloads and physical things. These choices are somewhat political and the majority of fellow travellers I have met try to live and act their varied politics within their work.

The Politics of Digital Publishing

Many of us have been involved with peer-to-peer (p2p) file-sharing via e.g. Soulseek and Torrents. This is nothing new. My dad used to order records in from the library and copy them to cassette. Him and his work mates would lend music to one another for the same purposes3. The digital equivalent has led to shifts, even within our small corner, and there is a tension between feeling like our digital works have little to no value and wanting music to circulate freely. How can something with a lack of physical tangibility, that can be instantly and perfectly re-produced, be worth anything? How can the output of our creative labour not be worth anything?

Lately p2p file sharing feels like less of an anti-corporate protest than gluttonous gorging. But let’s not forget the economies at play, especially with the everlasting aftershocks of neoliberal global economics, never-ending financial crises, ‘austerity’, and imminent #Brexitbus armageddon. Many of us can’t afford all of the nice things4 and sharing music amongst ourselves keeps ours, and our community’s, wellbeing loosely in check.

Snowden’s revelations highlighted the scale of state and corporate surveillance under which we are almost constantly subjected. Social media and advertising tracking cookies silently build shadowy profiles of our interests and engagements. Cambridge Analytica and Russian state interference exploit this to manipulate Facebook advertisers who remain complicit5. Similarly, electoral law is broken by the Brexit leave campaigns and we seem powerless to hold anyone to account6.

What emerges is a lot of power held in very few corporate hands, and especially in the hands of GAFAM (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon and Microsoft), within so-called ‘Platform Capitalism’. As individuals our clicks, our time, our engagement, and our content is monetised, frequently with little-to-no personal remuneration or benefit (we instead simply get access to the very services which are preying on us).

These same forces shape our DIY online publishing. As ‘content producers’ we utilise platforms to try and reach audiences, yet our content and interaction is monetised by the platform. We’re not making money from our junk clatter, field recording collages, drone-athons, and other deep excavations. Perhaps we don’t expect to make money anyway, so it doesn’t really matter. The pleasure of getting a random £4 on Bandcamp, the communities that we have formed, the trades facilitated, the gigs we found out about etc. far outweighs most of these negatives. How much do you really think GAFAM are making off of our tiny little pocket of the web?

The flip side is that we tolerate it because we have little choice. Yes, we can opt out (and many of us do refuse Facebook, take social media breaks, try and use alternatives etc.) but it’s not as easy a choice as that suggests. It comes at a significant price, especially if trying to share music within a community such as ours7. The logic of opting out disproportionately favours the already established over newer voices. How many of those newer voices have formerly been marginalised voices that will remain largely unheard if the only option is to opt-out? The idea we can solve these problems through market choice is a dead end – falling short of actually addressing the underlying power structures.

If it’s not about the money and we haven’t really got much choice, then what’s the beef? For me, specifically within our context, it’s about hegemony and power dynamics. We express a vibrant diversity across releases and approaches to publishing, yet frequently the solution to putting our work online is to put it on Bandcamp. I say this not to shit on Bandcamp (or us for doing so), but to highlight the one-size-fits-all solution that dominates most independent music communities. Bandcamp is great, it works brilliantly, payment seems fair, we’re not bombarded with adverts. I put my stuff on Bandcamp and it works really well for me. Bandcamp is great.

Some of us try and get our music on Google Play, Amazon, iTunes and Spotify. There are large hoops to jump through and costs associated with maintaining a catalogue with these services (via 3rd Party distribution). Costs and processes that fit much better with record labels (even small ones) than DIY, personal publishing. The remuneration rates are terrible so, for most of us, this will always be a loss leader8. iTunes, Spotify, Amazon and Google assume a role not dissimilar to the Major record labels. Bandcamp is more of an Independent. What’s worrying is that they seem to be pretty much the only Indy in the race9. That’s a lot of trust and power put in the hands of one organisation.

The hosting and buying of our music is only part of the publishing paradigm and again, much of this is dominated by Facebook Pages, Google Blogs and a handful of other social media platforms. I could make largely the same arguments about these services but shall refrain from repeating myself.

The Monoculture of Dominant Platforms

This lack of platform diversity also reinforces dominant monetisation, corporate and technological strategies. Spotify relies on subscription payments. Apple, Google, Amazon and Soundcloud offer similar services. Apple, Google and Amazon also offer traditional pay to download, with prices being mostly fixed and favourable towards the platform. Bandcamp is basically a similar marketplace where the rates for artists are much more reasonable and pricing is super flexible. All of these are organised as hierarchical, for-profit, corporate entities. Most come with subtle licensing restrictions10.

The ongoing state and corporate surveillance, referenced earlier, has led to far more public interest in using browser plugins and technological enhancements to resist corporate, digital profiling, and improve personal privacy. Subscription services can be hostile towards the use of Virtual Private Networks (VPN)11. None of the afore-mentioned music platforms are available via Tor Hidden Services, which are used by privacy advocates globally12. None of the services offer any p2p network technology (such as p2p browser protocols or mesh networks), meaning that in the extreme case of hostile state shutdown or government censorship they’d be done and dusted.

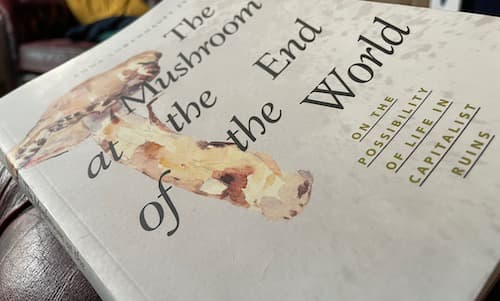

Some of these examples are getting extreme just for sharing 20 mins of dictaphonix vocal jaxx with ~30 fellow moong bean enthusiasts. These kinds of end-of-the-world scenarios come out not because of a lack of perspective, but because this is all intertwined with much larger debates concerning intellectual freedom, the need for an open internet, and risks of authoritarian power structures13.

Despite our variety of approaches to putting out hand-stamped CDrs, one-off lathe-cuts, wooden boxes made from discarded furniture; despite our numerous takes on sharing, trading, collaborative mail-art, selling from the car boot after a show, sneaking tapes into charity shops; despite all of this, digitally we use a handful of dominant platforms, pay via one of a handful of dominant payment processors and download a file directly from a centralised server system – all mediated by a handful of corporate behemoths. You could liken this to actual shops – they’re certainly dominated by a handful of large corporations – but even large chains such as the Co-op and John Lewis have alternative corporate ownership structures. Where are the alternatively structured music platforms, where’s the diversity, where’s the resistance to Neoliberal Capitalist Markets?

As the general shape of this debate has been running for quite a few years there are, and have been, a number of alternatives. It’s telling that many of the more viable ones generally come from a librarianship/archiving perspective (archive.org and freemusicarchive.org in particular), and whilst these easily facilitate the upload and sharing of your works, they are not really tools to promote, sell or market. They are repositories and not ‘publishing’ tools. A current alternative is co-operatively owned streaming platform Resonate (https://resonate.is) which is free to put your music on. You pay a small amount each time you listen to a track (loading up credits to cover your listening), and by the time you’ve played a track 9 times you’ve paid the equivalent of just buying it and so you now own it. So far, I’m a fan but it’s early days and still needs a bit of work. It’s not clear whether the above system will work or be anything more than a curiosity in a few years time. There are probably even better ideas out there and facets of the debate to which we are currently blind. My hope is that we take the time to explore them, remain open, and attempt the same levels of diversity in our online choices.

Before I get to my final position I’d like to make it abundantly clear that I don’t necessarily advocate ditching all of these dominant platforms. My own personal engagement has definitely mellowed over the last year. After ditching Bandcamp completely I came to regret it, have re-engaged again, and managed to sell a handful of CDs to some of you in the process. If it works for you use it. You don’t need me to tell you that, but it’s a message that often gets lost in this debate. I think that there are larger battles to fight and, if that’s your bag, you should consider supporting the work of organisations tackling state/corporate surveillance, and its related forms of power/exploitation, head on14.

If You’re Going to Do It Yourself You Should Really Do It Yourself, or Together

There are some other alternatives than can, and I would suggest should, be run alongside our use of the aforementioned platforms. There are many aspects of these services that we can run and create ourselves. This generally involves acquiring technical knowledge, broadly categorised within the computer sciences, such as programming, server administration and web development. These are seen as high-level skills that require significant investment of time and training to achieve.

I would suggest a far more amateur, DIY approach to these topics. Just as many of us learned a basic modicum of HTML to customise an online profile/template, the basics of running and maintaining simple web services ourselves is easily accessible. Speaking from my own experiences, I have engaged with all of the practices outlined below, and mostly I’ve poked and prodded until I could get something working. I never trained in any of these areas but have since acquired a functional, if uneven, body of expertise.

It is straightforward, and entirely possible, to run a small web-server from home, on a credit card sized computer called a Raspberry Pi, which costs ~£30. It is also possible to self-host an .onion version of this to harness the privacy enhancing features of the Tor Network.

Whilst there are still issues with dominant platforms, one can also easily and cheaply (often staying within free usage plans) run services on Google or Amazon Cloud Platforms (you’ll learn valuable skills along the way and define your own terms for publishing practices which can later be put to use with more ethical providers). If you begin to outgrow the above services there are far more choices, for Virtual Private Server providers, that won’t break the bank or your moral compass.

There are static site generators, such as Jekyll and Hugo, that allow you to produce fully featured websites with no need of complex backend systems and database installations. They do require some configuration and setup but, once the initial barriers have been overcome, the skills learned pay dividends.

Clubbing together to amortise costs and share resources could see a community offer a variety of services for little individual economic outlay. Or hook-up with a local group of internet privacy activists, get involved, volunteer some time and resources, and likewise get support with your DIY digital publishing using their servers/resources.

There are p2p browsers which avoid the need for web-hosting altogether. DAT (which uses Beaker Browser) and ZeroNet are currently the most viable. The biggest drawback is that if you turn your computer off the site will be unavailable but, the more connections you make the more your site’s hosting will be spread around your community and this would cease to become an issue.

It’s easy to make a torrent file of your own work and post this online, and you don’t need to engage with problematic pirate websites15. The benefits of legal torrenting within a small community seems very much inline with many of our offline practices.

I haven’t done any of this in a vacuum and neither should you: I have learned from online communities, tutorials and more knowledgeable others along the way, and likewise I try to share what knowledge I have16. Anyone is free to contact me if they need any help or advice17.

I also keep banging away at some of these ideas with The House Organ - https://thehouseorgan.xyz1819202122

I fully understand that many of us struggle with technology or are spread too thinly to even think about building alternative systems. Frequently these barriers lead to a certain fatalism regarding the whole subject. My biggest hope in writing this is that it might facilitate more of a debate within our community about such issues, and connect some people already working within this landscape. There are a number of aspects, regarding the current status quo of online DIY publishing, that seem counter to much of our politics and existing working practices, and I hope that collectively we might begin to approach building our own solutions. Who wants to explore these alternatives? Perhaps we can set-up some interest groups and/or resource sharing practices? Ultimately, I hope that our DIY practices expand more deeply into the way we publish and share our music digitally.

Erm… this is quite a one-sided format for such a discussion. Somebody else… Anybody… Say something…

Thanks

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0)

Kevin Sanders is always a source of critical thinking across these issues – i.e. his work with Radical Librarians Collective where I’d also name check Simon Bowie.

Andy Wood/TQ for supporting my work and giving me a platform for this supplement, and Isaac Ray for editing advice.

-

https://radiofreemidwich.wordpress.com/2015/06/14/what-i-mean-by-the-term-no-audience-underground-2015-remix/ ↩

-

I’m using DIY here as a proxy for the whole spectrum of Do It Yourself, Do It Together, self-releasing and small independent labels. ↩

-

Anecdotally they were industrial workers from the Midlands so I grew up with a lot of Heavy Metal and, despite an often scholarly rhetoric around intellectual freedom, I always associate file-sharing etc. with working class perspectives and the shop floor. ↩

-

Though let’s keep this in perspective considering the harm and violence of public cuts upon the vulnerable. ↩

-

I’m sticking here with UK news but there’s evidence of WhatsApp being similarly weaponised across the global south - https://tacticaltech.org/news/release-odos-whatsapp/ ↩

-

i.e. Investigative journalism of Carole Cadwalladr if you’re in any doubt as to any of these claims - https://www.theguardian.com/profile/carolecadwalladr ↩

-

I speak from experience here having destroyed the majority of my online and social media presence about 3 years ago, only really coming back within the last year fully, and noticing a significant difference in my ability to reach a small audience. ↩

-

Damon Krukowski provides an informative roundup of this landscape with the example of how some of the Galaxie500 back catalogue fares (and if they’re done badly by this system we haven’t a hope in hell) https://pitchfork.com/features/oped/how-to-be-a-responsible-music-fan-in-the-age-of-streaming/ ↩

-

Okay there are a few other services such as Tidal, Deezer, Pandora etc. but they fill small market niches within exactly the same structures as the afore-mentioned services. ↩

-

e.g. marginalisation which CC works may face by the distribution companies acting as gateways to major platforms - https://jelsonic.com/royalty-free/the-distros-dont-want-your-creative-commons-music/ ↩

-

Ostensibly due to geographic licensing restrictions and currently more prominent with video services i.e. Netflix. ↩

-

As a proof of concept I onionised Bandcamp though you have to jump through a lot of hoops to use it - https://mroystonward.github.io/onionised-bandcamp/ ↩

-

A great round up of digital privacy risks, and steps we can take to mitigate, comes from Extraction Music poster boy Kevin Sanders - https://rightsinfo.org/digital-privacy-protect/ ↩

-

e.g. Open Rights Group (https://openrightsgroup.org), Privacy International (https://privacyinternational.org), Electronic Frontier Foundation (https://eff.org) and Tor (https://torproject.org) ↩

-

The first time I did this I followed this guide - https://lifehacker.com/5534190/how-to-share-your-own-files-using-bittorrent ↩

-

I’ve been posting some tutorials at mroystonward.github.io ↩

-

Twitter (@mroystonward) / E-mail (murray.s.roystonward@posteo.net) ↩

-

tho2f4fceyghjl6s.onion ↩

-

dat:thehouseorgan.hashbase.io ↩

-

Source-code available at https://gitlab.com/thehouseorgan/thehouseorgan.gitlab.io ↩